Aging US highway infrastructure and a growing awareness of the harms these freeways represent have sparked a movement to remove them.

Some communities have relocated highways and replaced them with new houses, businesses, parks or other desired uses. Other communities have removed highways completely, replacing them with urban streets to more easily reach local destinations, plus hundreds of new houses and businesses. Where highway removal has happened, the trend has caught on. Citizens and cities have looked for additional opportunities to remove highway infrastructure. What follows are considerations and examples of successful highway removal efforts in North America.

Inner Loop East – Rochester, New York, USA

The 2.68-mile Inner Loop in Rochester, constructed in the 1950s and 1906s for a larger city, became a physical barrier between downtown and nearby neighborhoods. However, at the end of the century and as the region suburbanized, the Inner Loop was in disrepair and underutilized.

The idea for the boulevard conversion was included in the Rochester 2010: The Renaissance Plan in 1999. A study soon followed, but it took another decade and a federal funding source for the project to make progress. In 2012, a $17.7 million USDOT TIGER grant supported the removal of the Inner Loop East, a ⅔ mile section of the six-lane sunken highway, replacing it with an at-grade boulevard between Monroe Avenue and Charlotte Street, as well as bike lanes and on-street parking. The project was completed in three phases, with the first focused on filling in the highway and then building out the streets. Former and current mayors supported the plan as a tool to revitalize neighborhoods that had been damaged by the highway’s construction.

The removal of Rochester’s Inner Loop East was completed in 2017 and freed up nine acres for new development (estimated to support 430,000 to 800,000 square feet of mixed-use development), generating $229 million in economic development, creating over 170 permanent jobs and over 2,000 construction jobs. It also increased walking by 50% and biking by 60%. The removal allowed for mixed-use developments to break ground, including below-market-rate apartments. Streets have been reconnected across the former highway. As of 2023, nearly 500 housing units have been added in the form highway right-of-way, the majority affordable

Rochester is now planning for the remaining Inner Loop sections, including starting work on the Inner Loop North. In 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives approved $4 million in funding to transform Rochester’s Inner Loop North into a street-level boulevard. The project aims to reconnect northern neighborhoods to downtown and will cover study, design, and planning phases. The State of New York has committed $100 million to the project.

Park East Freeway – Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

In the 1990s, Milwaukee saw renewed interest in its riverfront with the development of a Riverwalk system along the Milwaukee River. This sparked a downtown housing boom, but the area around the Park East Freeway remained underutilized with parking lots and aging industrial parcels.

The Park East Freeway in Milwaukee was originally part of a 1960s plan to encircle downtown with freeways. The plan aimed to extend the freeway spur to the lakefront, connecting to I-794, was halted in the mid-1970s due to local opposition. Only a one-mile elevated segment was completed, leading to underutilization and blight in the neighborhood.

Recognizing it as a barrier to redevelopment, then-Mayor John Norquist campaigned for the complete demolition of the freeway. In 1999, collective approval was granted for the removal of the spur, and in 2002, using Federal ISTEA money and local Tax Incremental Financing, the removal process began with $45 million in funding from federal, state, and city sources.

The removal of the freeway and the introduction of at-grade six-lane McKinley Boulevard revitalized the area, restoring the previous urban grid. The City of Milwaukee, under the direction of City Planner Peter Park, drafted a form-based code to encourage development that aligns with the original form and character of the region.

Between 2001 and 2006, land values in the footprint of the Park East Freeway increased by over 180%, and within the Park East Tax Increment District, they grew by 45%, surpassing the citywide increase of 25% during the same period.

The Park East Corridor in Milwaukee underwent restoration, restoring the street grid that was interrupted by the Park East Freeway. The restored street network improved traffic flow and access to downtown. To date, the area has attracted over $1 billion in investment funding. The decision to tear down the spur rather than reconstruct it resulted in savings of an estimated $25 to $55 million in taxpayer funds.

Today, a new local group named Rethink I-794 is building on decades of local advocacy work and wants to see more projects like the Park East Freeway removal. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has proposed a $300 million rebuild of I-794 through Milwaukee and has plans to widen a 3.5-mile section of a nearby freeway to alleviate congestion. The Rethink I-794 initiative understands the futility of roadway expansion and is pushing for a different, proven idea: remove the highway altogether.

“It’s the difference between spending public money on things that cost more to maintain in the future and realizing that those things are not necessary anymore. […]We need to think about the long-term benefits rather than the short-term inconvenience of traffic congestion.” -Pete Park (Mendez, 2023)

Cypress Street Viaduct / Mandela Parkway – Oakland, California, USA

The Cypress Street Viaduct, California’s first double-decker freeway inaugurated in 1957, aimed to alleviate local road traffic and provide a direct route to the Bay Bridge. However, its construction severed the West Oakland neighborhood, contributing to the isolation of the predominantly Latino and African American population. In 1989, the Loma Prieta Earthquake led to the viaduct’s collapse, prompting a reevaluation of freeway investments in the Bay Area. San Francisco dismantled the Embarcadero and Central Freeways, while Oakland sought alternatives for the Cypress Street Viaduct.

Post-quake, the viaduct’s destruction redirected over 160,000 daily vehicles, causing congestion. Oakland engaged the community in reconstruction, selecting a new $1.1 billion route for Interstate 880 through an industrial area and railroad yard, avoiding residential and commercial zones. Simultaneously, the Mandela Parkway, a 1.3-mile boulevard, played a crucial role in reconnecting the divided West Oakland community.

Opened in 2005 with a $13 million investment, the parkway prioritized walkability, featuring 68 tree species, bike lanes, walking paths, grass lawns, and unique acorn-shaped light fixtures reflecting the city’s character.

Mandela Parkway catalyzed economic development, fostering approximately three dozen new businesses.

Between 1990 and 2010, West Oakland witnessed a 14% decrease in residents in poverty and a $5,720 increase in median household income. The removal of the highway resulted in health benefits, reducing annual nitrogen oxide levels by 38% and annual black carbon levels by 25%. The Mandela Gateway affordable housing project, established in 2005, provided 168 affordable-income residences, contributing to positive neighborhood transformation. Additionally, the parkway serves as a vital link in the Bay Trail, a planned 500-mile walking and bicycle trail around the San Francisco Bay. Beyond transportation, Mandela Parkway has become a community focal point, promoting connected and active urban living.

Unfortunately, rising housing costs in the Bay Area have pushed out long-time residents who would have otherwise benefitted from these changes. It has been reported that

“Black residents, who made up 73% of the population around the expressway in 1990, accounted for only 45% in 2010, according to Patterson’s research. Median home values along the parkway jumped by $261,059 in that time frame” (Digiulio, 2021).

Moreover, the highway wasn’t removed, per se, only moved to a less-residential, industrial area bordering the Port of Oakland. While air quality immediately around the footprint of the former highways has improved, the highway still runs through the City of Oakland, where trucks and passenger vehicles continue to spew noise and air pollution that impacts other residents around the city.

Bonaventure Expressway – Montreal, Québec, Canada

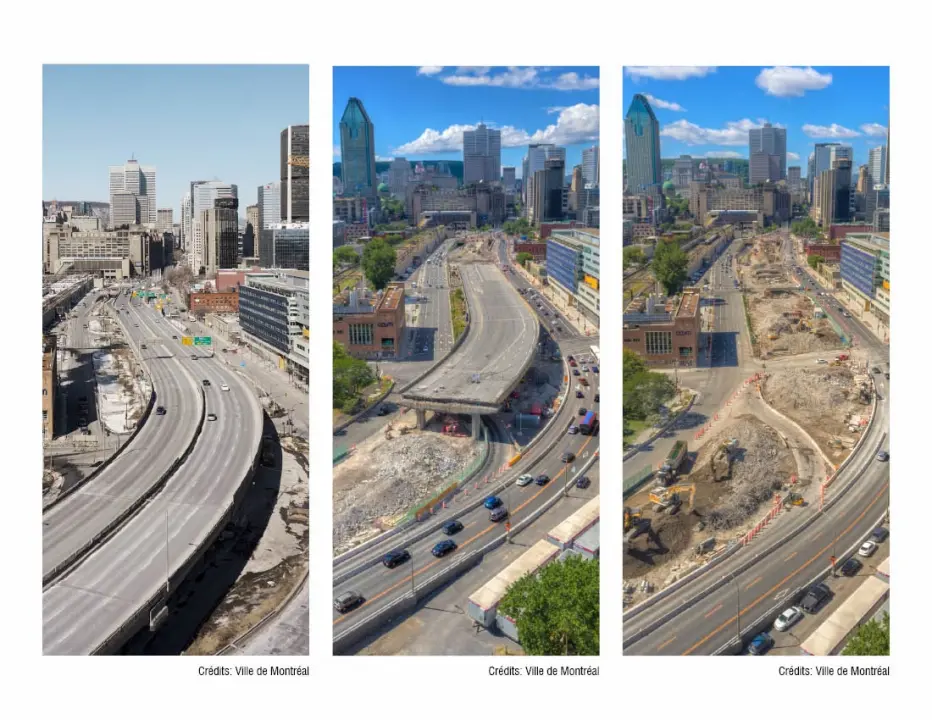

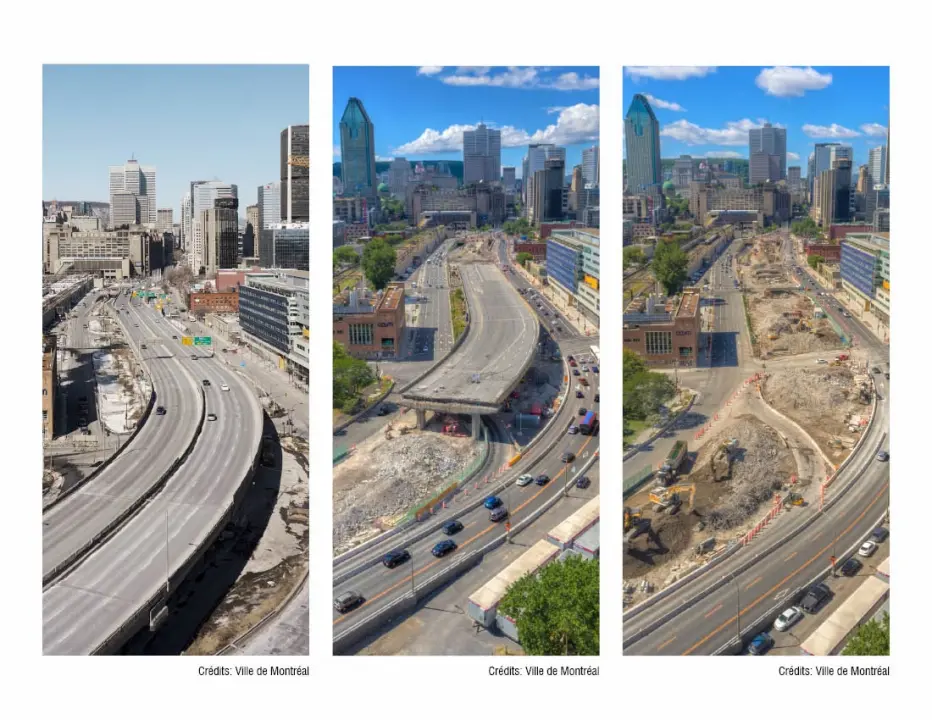

Built for the 1967 World’s Fair, the Bonaventure Expressway initially aimed to ease traffic into downtown Montreal. Despite Expo’s success, the 11-lane expressway became obsolete, hindering waterfront development, isolating neighboring Griffintown, and contributing to an auto-centric downtown.

The underutilized 11-lane expressway served 58,000 travelers daily. In 2002, Société du Havre de Montréal spearheaded harborfront redevelopment, exploring the transformation of Bonaventure into an at-grade boulevard. Of all the alternatives, the boulevard was chosen as the best option to reconnect the downtown area with the river, enhance waterfront development, and revitalize surrounding areas.

Projet Montréal began in 2011 and progressed through 2017, demolishing the expressway and introducing a light rail link. The $143 million project replaced it with two urban boulevards featuring green spaces, parks, and public art. An added $61 million was used to widen adjacent streets for additional traffic. The new street configuration allocated 65% of roadway space to active transportation and 10% to public transit, reducing motor vehicle allocation from 70% to 25%.

With this portion of the expressway replaced by more people-friendly streets and urban amenities, the City of Montreal is continuing its efforts to reconnect the city to its waterfront with recently announced plans to transform the non-elevated sections of the expressway as they reach the end of their design lifespan.

According to reports, this new stretch will: “The new lanes will overlap with Carrie-Derick St., which will be eliminated. The overall changes will reduce the road footprint and heat islands by 40 percent. Two active mobility paths will be built, including a river promenade for pedestrians and a multipurpose path that can be used by cyclists and skaters. Organizers said 650 trees will be planted, as well as 18,000 shrubs and 13,000 perennials. The new makeup will also provide better access from Pointe-St-Charles to the river.” (Bruemmer, 2023).

“Transforming a highway to bring it into the 21st century is a major project that doesn’t come around often and we seized the opportunity to ensure safe travel for all users. This new gateway to the city will directly contribute to Montreal’s attractiveness and the quality of life of residents of the area for generations to come. This is the result of a great collaboration with various partners, with whom the City of Montreal was able to fully share its expertise and its audacity.”

Valérie Plante, Mayor of Montreal

Ongoing Highway Removal Projects

There are a number of cities across the US and beyond that are planning to remove highways. Of particular relevance is the planned removal of Interstate 81 through downtown Syracuse, NY, as the preferred alternative that arose from this project has many parallels to the Twin Cities Boulevard.

I-81 skirts along the edge of downtown Syracuse, and similarly to I-94, it is heavily used for short trips to and around downtown. The removal of I-81 will require de-designation of I-81 through downtown Syracuse and re-routing I-81 to I-481 around the city. This project has recently completed the NEPA process with a record of decision issues in May of 2022. In the words of the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), the boulevard option was selected “based on a balanced consideration of the need for safe and efficient transportation, the social, economic, and environmental effects of the proposed transportation improvement, and the national, state, and local environmental protection goals.” The selected alternative, called the “Community Grid,” was also found to reduce VMT and greenhouse gas emissions.

This is not the first highway removal that the NYSDOT has undertaken. The removal of the Inner Loop highway in downtown Rochester, NY was completed in 2018. Since completion, redevelopment projects for the lands formerly in the right-of-way are providing housing and businesses. The success of this project is leading to the next phase of removal, the Inner Loop North.

NYSDOT has worked in stages to remove the Robert Moses Parkway from the City of Niagara Falls, NY, removing the barrier from the city to the gorge and removing an overbuilt and unnecessary highway.

Join us in contacting decision-makers.

Take action by emailing key decision makers and standing up for reparative justice.