Strategies to implement complete streets and reconnect communities are strong, but other strategies maintain a car-centric status quo.

In July, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) released a report to Congress addressing strategies, policies, and procedures the agency and other stakeholders aim to utilize in decarbonizing the U.S. transportation system.

This report arrives at a critical moment. As the Biden administration enters its final months, it sets the tone for the U.S. DOT’s future work on environmental issues. Its timing is also significant ahead of next year’s UN COP 30 climate conference, where new global emissions reduction targets and strategies will be established in Brazil.

With transportation accounting for a third of U.S. emissions, taking action now is vital for meeting global climate goals and safeguarding communities from environmental and health impacts related to transportation. The report hopes to shape both domestic policy and international commitments to meet 2030 and 2050 goals.

Within the transportation sector, light vehicles like personal cars account for roughly half of all transportation emissions, with medium and heavy vehicle emissions (mainly from trucks) accounting for 21%. These emissions mainly come from:

- Total amount of activity (distance and volume of travel for these vehicles)

- The energy intensity of transportation (energy per mile traveled)

- The carbon intensity of fuels used to provide that energy

In other words, this means that more cars traveling more distances and using intensive fuels (like gasoline and diesel) lead to more emissions.

A blueprint for transportation decarbonization

The report focuses on strategies on a blueprint for an inter-agency approach to reduce transportation sector emissions. These strategies include:

- Improving the convenience of green transportation options through transit, biking, walking, and changing policies that address land use, sprawl and excess parking

- Improving the efficiency of transportation including public transportation, intercity passenger rail, freight, and vehicle efficiency more broadly

- Transition to zero emissions vehicles and fuels through hydrogen, electrification, and clean energy generation

Combined, they aim to address distance traveled, energy intensity, and carbon intensity of transportation of people and goods, thus reducing overall emissions.

How will we accomplish these goals?

The strategies identified by DOT to accomplish these lofty goals are a mixed bag. Strategies for addressing efficient transportation and zero emissions vehicles focus more on interagency cooperation to roll out programs from a variety of agencies. These include electric transit vehicle programs from FTA, policies on sustainable fuels for cars, freight, and aviation, reducing infrastructure’s lifecycle emissions, and decarbonizing DOT operations.

However, strategies to improve green transportation convenience touch many transportation and land use conversations already underway in Minnesota, impacting state and local policies. Among these are smart growth strategies, part of recent fights on zoning, housing, and TOD, complete streets to improve pedestrian, bike and transit infrastructures, and transportation demand management.

Where are decarbonization strategies strong?

1. Complete Streets

Advising state and local governments to implement complete street design with universal principles for all non-car users improves safety and options for people taking non-car-based trips. These approaches range from ample lighting along streets and transit stops, dedicated bikeways and transit lanes, asphalt art and other traffic calming measures, and crosswalks.

This policy is reinforced through the U.S. DOT’s safer roads initiatives, but work to push state, county, and local agencies to pursue this work is essential to ensuring complete and equitable implementation.

2. Reconnecting Communities

The Reconnecting Communities program was highlighted as a strategy to increase non-car transportation convenience through its multi-pronged approach. The program is designed to study a variety of ways to reconnect communities divided by transportation infrastructures and promote multi-modal connection. The program provides $1 billion over 5 years to fund communities studying these efforts.

It is important to note that not all of these projects are truly transformative, with many prioritizing half measures like land bridges, highway caps, and other projects. For this program to do the most good in pursuing emissions reduction and community restoration, transformative projects like highway removal as funded in Duluth, Minneapolis, and in Syracuse and Rochester, New York must be prioritized.

What decarbonization strategies are strong, but need adjustments?

1. Smart growth and land use policies

Land use policies to promote density, like ending single-family zoning, parking minimums, and other policies, have the potential to create a more walkable, bikeable, and transit-compatible built environment. They also have the potential to build more housing in the central city, reducing need for long suburban commutes and reducing VMT.

However, many marginalized communities have been excluded from decision-making, risking displacement without targeted policies to protect vulnerable residents.While zoning reform in Minnesota is gaining momentum, anti-displacement efforts lag behind similar movements in California and Oregon.

Companion policies should be baked into these efforts. These companion policies should include rent control, Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Agreements (TOPA), Right to Cure Policy to avoid evictions, and Property Tax Transparency. These measures must be adopted in tandem with densification to ensure smart growth doesn’t exclude the same communities left behind in other policy interventions.

2. Transit investments and transit-oriented development (TOD)

As with smart growth land use policies, transit investments and transit-oriented development (TOD) must robustly engage with communities living along corridors and include anti-displacement policies to protect vulnerable residents. This has been an uphill battle in Minnesota. Local efforts like the Blue Line Coalition champions anti-displacement principles, while some transportation-focused groups oppose transit funding for studying these impacts on vulnerable communities.

The answer should not be withholding much-needed investments in transit-dependent neighborhoods, but anti-displacement frameworks must be co-created with communities to ensure these policies do the greatest good in advancing equity and climate goals.

3. Pricing measures are effective, but U.S. cities have shied away from them.

The report cites congestion pricing, gas taxes, and fees for driving as an effective strategy for reducing personal vehicle use and they are right to do so. Mode shift priorities are not just related to land use and transportation provisioning but also must include measures for individuals to internalize the social cost of driving by paying fees that both reduce people’s tendency to drive but also fund important public and active transportation investments.

The problem in the U.S. is feasibility. Cities around the world have pursued these policies including Singapore, Stockholm, London, and Milan, cities that all have congestion pricing measures. However, New York City made an eleventh-hour reversal from its own congestion pricing policy in June with huge implications. And a gas tax, while effective, seems unlikely given the oil industry’s hold on federal policymaking.

Where do decarbonization strategies fall short?

1. Goals to fix existing highways ignores their impacts.

The DOT does well to acknowledge the realities of induced demand along highways, meaning adding more lanes actually means worse traffic and increased vehicle miles traveled (VMT). However, prioritizing maintenance of existing highways over highway expansion does not go far enough in addressing harms, both local and global.

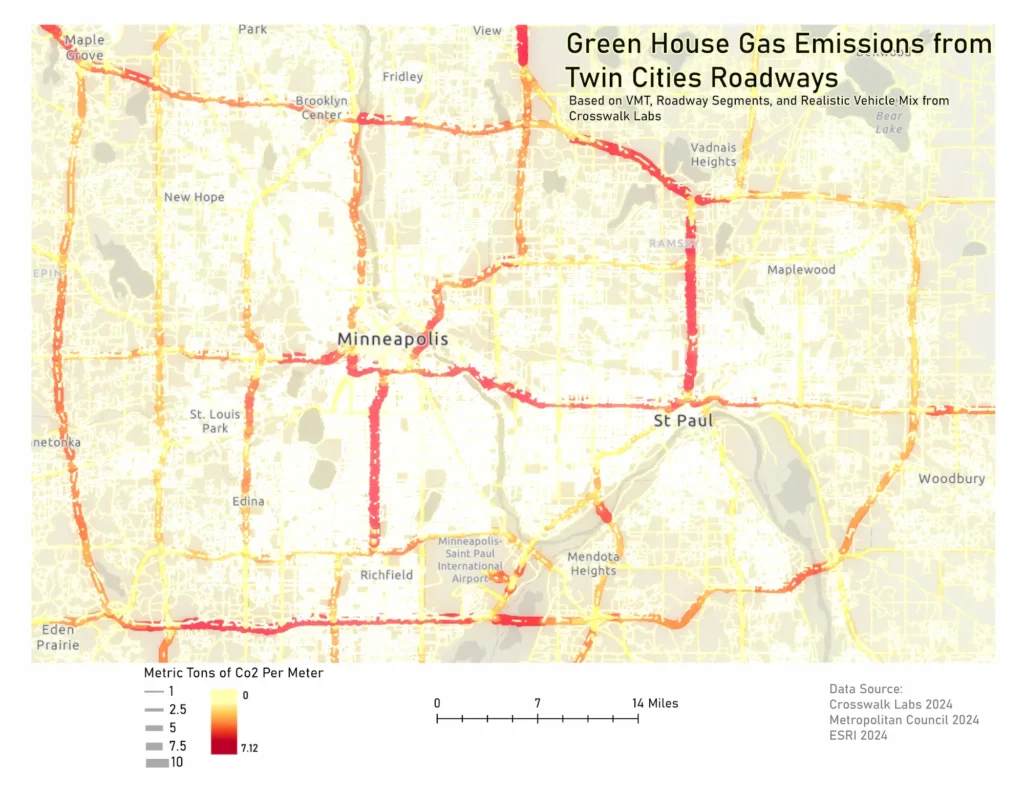

In the Twin Cities, emissions from vehicles traveling along highways accounted for two-thirds of our region’s transportation emissions according to research by Crosswalk Labs. This means that prioritizing maintenance on highways that will extend their life will prevent us from making meaningful gains in greenhouse gas reductions through VMT reductions.

A truly transformative project would go beyond mitigation and focus on strategically removing highways and replacing them with diverse transportation corridors, reconnecting the street grid, and promoting community-driven development. While this may seem aspirational, thoughtfully crafted highway removal strategies can be practical, not radical.

2. Electrification is not a silver bullet.

The report focuses heavily on the electrification of vehicles and infrastructure investments to support this transition, but electrification is not a silver bullet. Electric vehicle components come with significant environmental and social impacts for communities around the globe. They also still pollute PM2.5 particles dangerous to local community members and charging infrastructure and purchasing opportunities still don’t reach low-income communities.

Effective implementation requires federal commitment and community representation.

The implementation of these policies will be helped by the U.S. DOT through grants, partnerships, policies, and technical assistance. However, important to note is that these policy frameworks could be cast aside depending on the goals of the next administration.

Some DOT programs including reconnecting communities are already being cut back, with the federal government shortening the program from five to three years and putting all remaining funds on the table this year.

To ensure just implementation and to maximize policy benefits at all levels, vulnerable communities need a seat at the table. Locally, this means increased engagement, creative placemaking, and collaborative problem-solving for transportation, housing, and land use challenges.

The impact of these policies extends globally, too. Future Republican administrations are likely to withdraw from the UN climate change framework, mirroring the U.S.’s exit from the 2015 Paris Climate Accords under the Trump administration. As new global climate policy guidelines are set for negotiation next year, it’s crucial to demonstrate policy leadership and effectively reduce emissions in our largest polluting sector – transportation. This commitment is essential at federal, state, and local levels.